My wife and I are usually in bed before the 11 o'clock news, so we seldom see what passes for local news in Baltimore. However, on Friday nights after watching one of our favorite shows Numb3rs, we sometimes linger on Channel 13 and catch the first segment of Eyewitness News. This is often accompanied by our own home version of Mystery Science Theatre 3000 as we watch the unintentionally hilarious circus that supposed to be serious news:

"Why is Dennis Edwards standing in front of the county police headquarters at 11 o'clock at night when the crime he's reporting on occurred this afternoon? Go back to the TV station, Dennis, it's cold outside!"

"Why is Bob Turk reporting the weather from the WJZ-TV parking lot? We don't have to see your breath to believe that it's in the mid-20s right now!"

"What do you mean there are no details about the shootout on North Avenue? How much you wanna bet at least one of the victims is a drug dealer?"

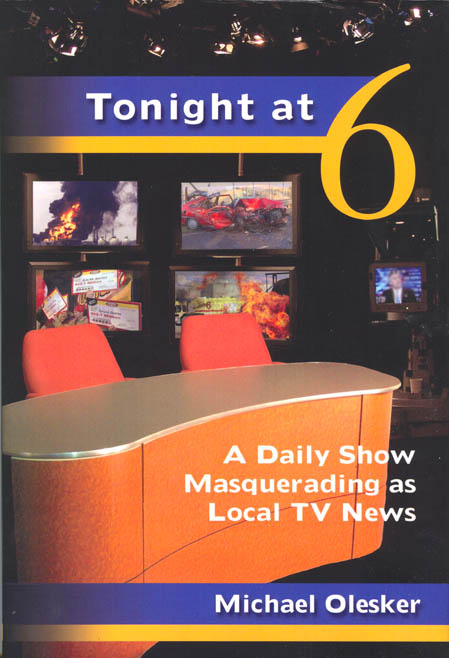

Oscar Levant, the remarkable pianist, composer, actor, and alcoholic, called the old news reels of his day "a series of catastrophes, ended by a fashion show." Watching the nightly shows, it doesn't look like we've advanced any since then. A typical Eyewitness News report consists of shootings, fires, car wrecks, and general mayhem from around the globe finished off with some feel-good piece about a dog who saved his 80-year-old master from choking to death. By the end of the show, you feel distraught but somehow no more enlightened about your community than you were before the broadcast. Such is the point of journalist Michael Olesker's book Tonight at 6: A Daily Show Masquerading as Local TV News.

For almost 20 years, Olesker provided a commentary five nights a week on WJZ's newscast. In 1983 when he started his gig, he was already a well-known columnist for The Baltimore Sun, providing daily insights into the pulse of Baltimore and its neighborhoods. WJZ had the hottest TV newscast in the city, thanks to the amiable rapport of its two anchormen Jerry Turner and Al Sanders. Olesker seemed to be plunked in as a way to bring some respectability to a newscast that was considered long on the warm and fuzzy, but short on real news. No one seemed to care, however, because everyone liked Jerry and Al so much. Two middle-aged men, one black-one white, one dignified authority figure-one the affable jokester, who created ratings magic, often pulling in more viewers than the other two major stations combined. The city loved Jerry and Al, and as long as they were delivering the news, no one questioned the vapid quality of the content.

TV news is, after all, about visuals and emotion rather than content and insight. Show the scene of the murder with police car lights flashing and the outline of a body on the cold, wet asphalt. Cut to the grieving mother who has just lost a son barely out of his teens. It's raw, it's emotional, but how does that help the person sitting at home watching the broadcast. From Olesker's point of view, the high murder rate in Baltimore needs to be reported in the context of the root causes such as high unemployment for black males, underachieving public schools, and a shrinking blue-collar base. Television news can't be bothered with such details. They have to send a film crew out and get pictures. The "reporters" in TV news are actually broadcasters who know TV, but very little about journalism. Stick a mic in someone's face and ask questions, then put it on the air. No time to check facts or dig for an angle. Just make it look good.

I got my first taste of how TV news works when I was doing public relations for a community college. I would send out press releases to the local TV stations if I thought a story had visuals that might interest them or involved politicians or other well-known people. If one of the TV stations contacted me about coming out to do a story based on my release, they would often dictate when they were coming. It was up to me to line up key people for them to interview and make sure things would be happening that they could film when they arrived. I also had to compile background material and send it to them ahead of time. At the designated time, the reporter and a cameraman would breeze in, whereupon I would have to take them to where they would interview the key contacts and film whatever it was that would look good on the news. Surprisingly, most people were more than willing to accommodate the demands of the TV crew. They would be on television, after all. That night on the news, I would see a reporter reading lines into the camera that were lifted directly from my press release, followed by snippets of the interviews and various shots. After all that work on my part, the piece would last less than 90 seconds. It didn't matter to anyone that the reporter was taking credit for other people's work. We got on TV.

Olesker points out that much of TV news is that way, with stories often lifted verbatim from the daily newspaper. Despite all their claims of "team coverage" and "in-depth reporting," most of it is shallow at best and down right inaccurate at worst.

Channel 13 lost Jerry Turner to throat cancer in the late 80s, and Al Sanders passed away a few years later. They were replaced by Denise Koch, an actress who started at the station doing hang-gliding and surfing segments called Daring Denise, and Vic Carter, a tongue-tied newsreader from Atlanta who was known at his previous station as "Bryant Stumble." The ratings for Eyewitness News over the past decade or so have slipped severely, often beat out by Channel 11's Action News, which decided to do something crazy and focus on (gasp!) journalism. But Channel 13 continues to stumble on with their style-over-substance approach.

Tonight at 6 is a wonderful book for those who have lived in Baltimore for the last several decades and remember the days of Jerry and Al, but I'm sure anyone in the U.S. can relate to these anecdotes of vapid local news. Every major city has an Eyewitness News or an Action News, and it's all about the same. The bigger question from Olesker's book is why the great champion of journalistic integrity stayed at the station for 19 years. He answers in a cursory way, citing the fact that he had to feed his family and that his commentaries had nothing to do with the news portion of the show. Fair enough, I suppose. He also points out that he did complain to management once in awhile, but that hardly justifies staying in a system he despised for almost two decades. What makes that even more disturbing is that he never had any intention of writing about it until he was fired. He was willing to play along if the checks kept coming. Once that stopped, he would cash in with a book. Somehow all this taints his integrity even as he attacks the integrity of his former co-workers.

Still, if you are someone who is exasperated with the stupidity of television news, Tonight at 6 can be a cathartic read.

No comments:

Post a Comment